It’s no secret that I am the world’s biggest advocate of the Jefferson Deadlift (or Jefferson Lift, or Straddle Deadlift, or Jefferson Squat). In 2012 I set the IAWA world record for the Jefferson at 605lbs. I have personally taught hundreds of people how to do this lift, and written several articles on the topic. I want you to at least try it, because it’s a fantastic lift.

My obsession with the Jefferson started a few years ago when Adam T. Glass suggested that I might have good natural leverage for it. We looked up the lift in the record books, and realized I could probably break the world record, which I later did in a training lift in 2011 and officially in a contest in 2012.

When I first met Jen Sinkler, she couldn’t conventional or sumo deadlift without pain. The Jefferson was one of the main lifts I prescribed for her to test out, and sure enough she was out of pain and back to traditional deadlifting for a PR in just a few months. Since then I have used this lift to help get countless people out of back pain. Plus, the total-body strength you develop with this lift is awesome.

Why?

Let’s get the reasoning for doing this awkward looking lift out of the way first. Here’s the short version: because you’re weak. Maybe that’s not entirely fair, but I’d be willing to bet it’s true that you are weak outside the ranges of motion that you’re accustomed to. For most people, these are very saggital-plane dominant squats and deadlifts. There’s no rotation, there’s no anti-rotation, and there’s no strength in asymmetry. Before you tell me how those are good things, let me warn you that I have a roster of people who can speak to how Jefferson lifts played a starring role in taking them out of back pain. Further, I’ve personally seen people tweak something conventional deadlifting, and I have never (knock on wood) witnessed anyone hurt anything doing a Jefferson.

The Basics

More Advanced Tweaks

One of the neat things about the Jefferson lift is that it’s already so weird and awkward, it’s impossible for anyone to pin down what “perfect form” is for it. As such, people default to finding what actually is the strongest leverage for their own body.

However, it’s worth discussing what features of alignment make for the strongest pull. In my experience, the more like a trap bar deadlift (with a rotation) you can make it, the stronger you’re going to be. Alignments that favor one leg significantly don’t work as well.

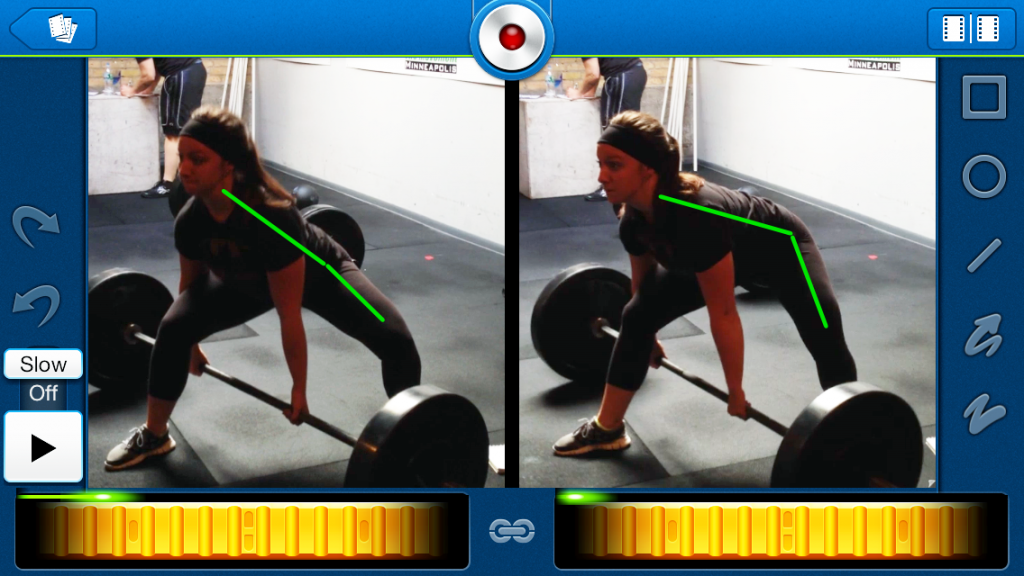

In this comparison photo, you can see in the second photo Abbie’s hips are starting much higher, her back is flatter towards the ground, and the angle between her back and legs is much greater. She is also leaned forward heavily over one leg. For her in particular, to correct this, I asked her to take a position with more external rotation of the feet as in a plié. Being a dancer, this is a position that is strong and comfortable for her.

This resulted in an immediately stronger pull that felt much better for her.

Here is a checklist to use to find better alignment:

- Are your heels staying planted throughout the lift? If not, adjust so that they are.

- Are your hip starting in a high position, that you could lower by adjusting your feet? (Hips high is relative, the question is, can I get lower?)

- Are you fighting rotation on the way up? Could you start in such a way that the bar is already rotated to where it’s going to end?

- Is the bar hitting the inside of a leg? Adjust your position, sometimes it helps to rotate a little more along the hip axis, so that the bar travels smoothly up in between your legs.

- Are you mixing your grip on one of your hands? This typically helps, and most people are more comfortable in a mixed grip with the front hand turned palm facing out (supinated.)

Curious about how to integrate the Jefferson deadlift into your training to make your pulling strength downright impressive? This and dozens of other variations in my deadlift book, Off The Floor, will catapult your strength into another dimension. In addition you’ll learn to use biofeedback, giving you an unprecedented blueprint for success in your training. This is the exact template I used to skyrocket my deadlift from a measly 245 pounds to not one but three different 600+ pound deadlifts in 3 variations, including a world record.