Sweat pouring off your brow, bent over with your hands on your knees, head pounding, lungs aching with just a hint of the taste of blood in your mouth.

Great conditioning session, right?

At least that is what you have been told. It needs to be hard — in fact, it needs to be brutal. You should be begging to be finished and wishing it was the end.

Except…what if I told you it could be easy? I think it can be. But let’s start from the beginning.

Conditioning 1.0

The traditional approach to conditioning is to have either a set amount of work to be done, or a set amount of time to work for. This might look like a circuit where you do a certain number of reps per exercise for a certain number of rounds, or an “AMRAP” where you work for as many rounds as possible for X number of minutes.

The exercises that comprise the work are usually coordinated to spread the work out evenly over the body without overloading any particular part. If you’re training for a specific sport, ideally the movement will be specific to the sport. For example, a large part of a rugby player’s conditioning might be exclusively sprinting since that makes up the majority of their sporting movement.

If you’ve been following what I write about for any length of time, or if you’ve been through my free Gym Movement eCourse, you might immediately recognize the problem.

The problem is that everything you’re doing is arbitrary. The movement may not test well, you might be doing it for too many or too few reps, and you might do too much or too little total work. More often than not, conditioning work is done in a distress manner. You may remember from the GM eCourse that eustress is stress that is easily resolved. A workout with a tested movement done without elements of effort only until it doesn’t test well is a eustress workout. A distress workout is an untested movement done for an arbitrary number of sets and reps regardless of how it tests.

Why is most conditioning approached in a distressful way? I think the answer to that lies in a remark Frankie Faires made to me once, which has borne out to be completely accurate:

“Results happen faster under distress, both intended and unintended.”

In other words, yes, your conditioning will improve more quickly under distress conditions. Right up until the point of injury, burnout, etc.

A minimal effective amount of distress training is necessary and useful for athletes because even though the needs of an athlete are largely predictable, there is always some degree of uncertainty in competition. Sometimes you just have to do the work, whether or not you’ve prepared for it within the boundaries of your training.

What if we approached conditioning from a different perspective, in a smarter way?

Before we look at how we can do this better, I’d like to define the purpose and intent of conditioning clearly.

For what purpose?

The only practical purpose for conditioning is to increase the amount of work a person can do in a given amount of time. This can be either for a sport, in which case the amount is dictated very clearly by their sport, or for general physical preparedness, in which case the amount is the minimal effective. In the context of the majority of the people I train, they need to be able to run through the airport to catch a flight without getting winded. Not much more.

We do not ever use conditioning as a tool for fat loss.

When it comes to sports, the parameters are often very clearly defined. People like to talk about how athletes need to be prepared for anything, but that is utter nonsense. Sports have rules, and rules clearly define the boundaries. Take rugby, a sport for which I have trained many athletes, for example. There is lots of data on rugby work volume, and it speaks very clearly. The greatest distance run in a rugby match is seven kilometers (five miles.) We know that matches last about 80 minutes, which gives us an important set of parameters. We now know that a rugby player doesn’t need to be able to run more than 7 km in 80 minutes. Of course that’s not much to go from, but there’s more. From the studies of game data that have been done, we know that 67.5% of the sprint efforts are under 20 meters (about 30 per match), and that they are followed by long (greater than five minutes) recovery. Sprint efforts over 40 meters only occur less than 10% of the time, or less, depending on position.

Without turning this into an article on rugby conditioning, you can see that a picture emerges very quickly about what a rugby player actually needs to be able to do. There is very little mystery.

You can disassemble any sport you want and determine very quickly what they need to be able to do and how much time they have to do it in.

On the other end of the conditioning spectrum, if you are simply doing conditioning for general physical preparedness, you have an even more clearly defined parameter for where to direct your training: wherever you are. Start with what you can do, and seek to do more if it in less time. You’ll know you’ve done enough when you don’t get winded doing everyday tasks.

Conditioning 2.0

Now that we’ve established our purpose for conditioning and we have a pretty good idea of the parameters of our training for sport or life, we can get to the actual training. As I mentioned earlier in the article, much of what people do for conditioning is totally arbitrary. Randomly selected movements done for an arbitrary amount of reps for a pre-determined amount of time. Not best.

If you’re at all familiar with the biofeedback testing approach I teach, you could imagine that we might be able to test some or all of the parameters of the workout. If this is new to you, the shortest version is this: why not look for a physiological or biometric marker to determine if something is good or bad for us in real-time? This approach works exceedingly well in strength training, and though less often applied, it works just as well when it comes to conditioning work.

The big mental paradigm shift is that conditioning work is not special — we are simply looking at optimizing a different metric from strength work, which focuses on intensity, whereas in conditioning we are optimizing for density.

Once you understand that, you can take into account an acceptable degree of distress and intelligently design the workout to suit the needs of the individual.

In the case of general fitness or GPP we can maximize the eustress approach because we want to optimize progress, minimize unwanted effects like injury, and there isn’t an unknown that we need to be prepared for. Do what you can.

On the more athletic end of the spectrum, we can use more distress training to elicit faster response and to create more capacity for performing in distress. I want to be clear here: the maximal effective amount of eustress training and minimal effective amount of distress training still applies to athletes.

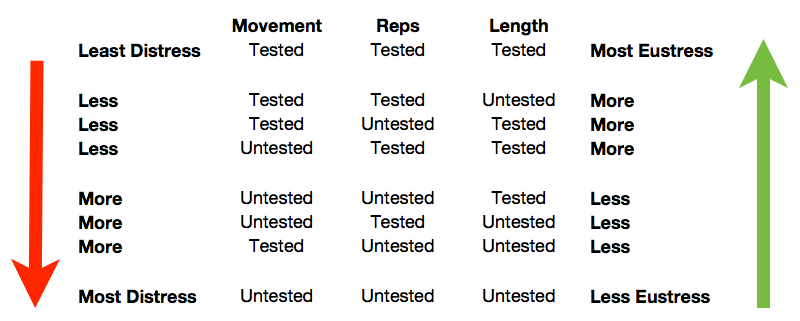

To create a conditioning workout you have three parameters to work with: the movement(s), working time (time interval or number of reps), and total length or time, which is a proxy for your rest.

Here’s an example conditioning workout:

10 sets of 10 burpees, as fast as possible.

Or

As many rounds of 10 burpees as possible in 10 minutes, resting as necessary.

How could we make this into a more intelligent workout?

For starters, we could use a tested movement instead of burpees. If they didn’t test well, we could test bodyweight squats, for example.

Next, instead of setting a rep count to 10, we could simply set the parameter “do as many as you easily can, then stop.”

Finally, instead of setting the total volume at 100 or setting the time to 10 minutes, we could test after each round, stopping whenever the tested volume of work occurred.

In three small changes we’ve transformed this from an arbitrary and possibly harmful workout into a fully tested eustress workout.

Without further ado, here is the matrix I designed which was the genesis of this article:

As you can see, you have eight different ways you can structure a workout from completely tested to completely untested.

As you can see, you have eight different ways you can structure a workout from completely tested to completely untested.

A fully eustress conditioning session can be downright easy, working within your limits to expand your limits. To move it a little closer to distress training, you might opt to select an untested (or purposefully poorly testing) movement but maintain eustress parameters when it comes to the actual work output.

Ultimately, the choice is yours and only yours. Disregard the cookie-cutter program — using this framework, you can become your own n=1 experiment and develop your own best conditioning system.

P.S. This week ONLY! I am going to GIVE AWAY my book, Lift Weights Faster and Smarter which expands on the ideas in this blog post and completely lays out for you exactly how to make 20 workouts hit the precise stress target you need to EVERYONE who buys Lift Weights Faster during the last chance sale. With LWF2 on the horizon you will never again be able pick up the critically acclaimed first Lift Weights Faster on its own – much less at 50% off like it is this week. My advice? Nab it while you still can and you’ll score Lift Weights Faster and Smarter for FREE.

P.S. This week ONLY! I am going to GIVE AWAY my book, Lift Weights Faster and Smarter which expands on the ideas in this blog post and completely lays out for you exactly how to make 20 workouts hit the precise stress target you need to EVERYONE who buys Lift Weights Faster during the last chance sale. With LWF2 on the horizon you will never again be able pick up the critically acclaimed first Lift Weights Faster on its own – much less at 50% off like it is this week. My advice? Nab it while you still can and you’ll score Lift Weights Faster and Smarter for FREE.