When I go to a conference or workshop I hear two types of feedback from people. Either they’ve implemented biofeedback in their training and gotten the best results (whether that be pain resolution, or performance) of their life, or they can’t figure out how to get started. Jen, too, hears the same thing often.

Here’s the deal: This is not something you can think your way through. You have to take action, and you have to implement. In nearly every conversation I have with someone who reports that they haven’t been able to figure out how to get started they have tried to think their way through how it might go instead of simply trying it and going from there. What you need to understand is that this is a paradigm shift in how you train and you can have no idea how to wrap your head around it because you’re coming from an existing, and incompatible paradigm.

The vast majority of exercise programming is based on you following the program. You just do what it says. Biofeedback or intuitive training involves completely flipping the operating system and following where your body leads.

What do you need to implement biofeedback training? Three things:

- Stimulus

- Response

- Test

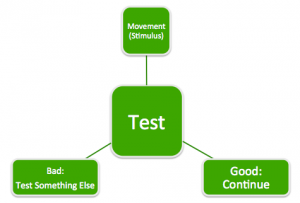

That’s it, at it’s core. You need a stimulus, a response, and a way to test or measure what the response is. Of course in any exercise protocol you have a stimulus (the exercise) and a response (the recovery, regeneration, gainz, etc.) The piece that is lacking is the test.

Is this good for me to do?

Exercise isn’t automatically and universally good. This is too complex a topic to hash out here, but if you’re struggling with this concept consider this: is it good to do deadlifts if they cause you pain?

Response to exercise can take weeks and months to be able to quantify. At the very shortest, you don’t know if it “worked” until you do the movement again and do better than before. The response is so far out into the future you could be doing the “wrong” things. So the question you want to be asking is, what would be good for me to do? Is this good for me to do right now?

Enter biofeedback testing:

We use range of motion testing as our test. Click the link for a walk-through video. Other methods can be useful, but in the interest of keeping it simple let’s just stick with ROM. The idea being that we can test to determine, on a very short time scale, what the response is right now. Based on the response of the stimulus, you can decide to continue it or not. Do things that garner a positive response in the short term, and over the long term you have an accumulation of positive responses.

We use range of motion testing as our test. Click the link for a walk-through video. Other methods can be useful, but in the interest of keeping it simple let’s just stick with ROM. The idea being that we can test to determine, on a very short time scale, what the response is right now. Based on the response of the stimulus, you can decide to continue it or not. Do things that garner a positive response in the short term, and over the long term you have an accumulation of positive responses.

One source of confusion is the baseline testing before the movements or exercises. Testing your baseline is like calibrating your measuring stick. If you don’t figure out where you’re starting, all the measurements that follow it are useless because you have no basis for comparison.

How to put this into practice:

- Test your baseline.

- Perform a movement.

- Test again.

- Based on the result of the test, continue or do something else.

As I mentioned before this must be put into practice. Stop thinking it through and do it. Here’s how you can implement it in your own training immediately: Take your existing program, and test everything before you do it. Test the movement; Do it if it tests well, and don’t do it if it doesn’t. Either skip it or test a similar variation. Test your weights. After each set test to see if you should continue to increase the weight. If you’re at your working weight then stop doing that exercise when you get a negative range of motion test.

While this does represent a major shift in how you approach your training sessions it is absolutely elementary in application practice. Try it – then review your training progress for four to six weeks. Applied correctly, this will make a profound difference.